From Chaos to Calm: Five Micro-Regulation Practices Every Teacher Can Use in Under Two Minutes

The Emotional Cycle Is Faster Than We Think

One of the most reassuring pieces of neuroscience for educators comes from Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor, the Harvard-trained neuroanatomist famous for her work on the brain and emotional processing. She teaches that when an emotion is triggered, the biochemical wave of that emotion moves through the body in about 90 seconds. If nothing is added to the story — no rumination, no reinforcement, no shame spiral — the emotion completes its cycle and begins to settle.

Ninety seconds.

For a child, that window is everything.

For a teacher, it is the difference between escalation and reconnection.

There’s only one small problem: most students don’t know how to move through those 90 seconds and most adults don’t even know this window of time exists because they’re so used to interrupting the loop and ‘storing the story’. Bodies flood with energy, systems go into protection mode, and before you know it we’re swept into behaviours that are really just attempts to regulate discomfort. And this is exactly where micro-regulation becomes a lifeline. Small, body-based practices help the nervous system return to safety long enough for the brain to process what’s happening. These strategies are grounded in what we know about the autonomic nervous system, sensory integration, and the ways children re-establish a sense of internal stability.

Here are five research-backed micro-practices teachers can use in real time (no equipment, no prep, no drama) to support students through that 90-second window and back into themselves.

Clay is the ultimate grounder

1. The Clay Moment: Proprioceptive Reset Through the Hands

One of the fastest ways to shift a dysregulated nervous system is through proprioceptive input, the deep pressure signals that come from muscles and joints. Occupational therapy research shows that proprioception has a stabilizing effect on the autonomic nervous system and can support children through overwhelm far more effectively than talk, light-touch and/or visual stimulation.

A small piece of clay (even the size of a grape) gives the hands a source of steady, grounding pressure. When a child squeezes, rolls, presses, or shapes clay, the body receives deep sensory feedback that helps the brain recalibrate. This type of proprioceptive input supports the parasympathetic system, quiets motor agitation, and provides a physical way to complete the emotional cycle. For many children, the nervous system begins to settle within seconds of utilizing clay.

Clay works because it gives emotions somewhere to go. It meets the body in the exact language it understands: weight, texture, resistance, movement. All of this signals safety so the body begins to downshift from stress and come back to a centered state. And we know that it is only when a student is in ventral vagal that the mind is capable of learning.

2. Slow Linear Walking: Bringing the RAS Back Into Regulation

The Reticular Activating System (RAS) acts like the brain’s alertness dial. When students are wired, scattered, or unfocused, the RAS is often over-activated; imagine an alert German Shepherd who scans the landscape for any sign of threat. Slow, predictable walking helps reorganize this system by providing bilateral movement, proprioceptive rhythm, and a consistent sensory pattern for the brain to orient to. In essence, our inner German Shepherd is able to stand down, when the brain is focused on movement.

A simple walk across the classroom — slow steps, heel-to-toe, eyes soft, breathing steady — can bring a child out of hyper-alertness or shutdown. In the Neurosequential Model, (Perry, 2006), rhythmic, patterned movement is identified as one of the most effective ways to help the brain shift back into its learning state. Even thirty seconds of slow walking can help the body transition out of reactive mode. This is why the old advice of going for a walk to cool off, or clear your head is effective. Walking helps settle the RAS and bring the whole body back into a learning state.

But what does this look like in the classroom?

Simple, students who need a break are offered a slow lap around the room, or given an errand/delivery to make to the office or another classroom, or walk to a set point like the library and then come back. Students can bring their focus to counting footsteps, moving slowly, and their breath. The goal isn’t to shift into “monk mode”, but rather to give the brain and body space to process the heavier stress/discomfort, complete the cycle and then come in refreshed and ready to learn.

Wall Pushes

3. Wall Pushes for Autonomic Stability

Wall pushes are one of the simplest ways to help a child settle their nervous system, and the body responds to them faster than most people realize. When a student places their palms on a wall and gently leans in, they activate the proprioceptive system — the deep pressure and joint feedback that occupational therapists rely on when a child is overwhelmed. This kind of steady pressure has a calming, organizing effect because it brings the body out of the swirl of fight-or-flight and into a more grounded sense of presence.

The movement itself matters. It’s slow, predictable, and rhythmic, which aligns with Bruce Perry’s research showing that patterned, repetitive activity helps the brain shift out of stress activation. Wall pushes also engage large muscle groups, creating a sense of stability that the nervous system interprets as a cue of safety. Children who feel scattered, impulsive, or emotionally flooded often settle within moments because the body finally has a clear, contained way to release excess energy.

What teachers usually notice is small but meaningful: the child’s breathing deepens, their shoulders drop, and their gaze becomes more focused. This is the first sign that they’re moving closer to ventral vagal, the state where connection, problem-solving, and learning become possible again. Wall pushes don’t require equipment or explanations — just a gentle invitation to press, breathe, and let the nervous system recalibrate. The body does all the heavy lifting.

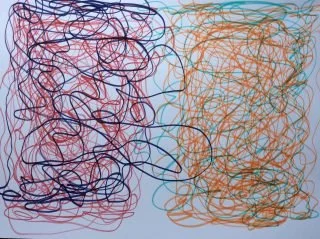

Bilateral Scribbling with Crayon

4. Bilateral Scribbling for Integration and Focus

Bilateral scribbling is a fast nervous system reset that organizes the brain through simple, mirrored movement. When a child uses both hands at once — even for a minute or less — the sensory system receives coordinated input that supports regulation. In Sensory Integration Work (Ayres, 1972), bilateral coordination is linked to improved emotional stability because it strengthens the pathways between the hemispheres and helps the brain process overwhelm more efficiently.

This doesn’t need to look like a full art activity. In fact, it works best when the movement is loose, quick, and pressure-free. A child can pick up two markers (or crayons), one in each hand, and create mirrored lines or looping shapes without thinking about what they’re drawing. The focus isn’t on the picture; it’s on the rhythm. Within seconds, the nervous system begins to track the repetitive motion, and the excess energy that comes with stress starts to settle as the student draws.

Teachers often notice small but meaningful shifts — a deeper breath, a softened jaw, or renewed eye contact — as the brain moves away from chaos and toward something more organized. Even sixty to ninety seconds is enough to help a student reconnect with their body, reduce internal static, and return to the classroom task with more steadiness. It’s quick, quiet, and incredibly effective for kids who need to reset without leaving the room. It’s also a fantastic tool to use during Guided Instruction if your students are struggling to begin reading or writing. The bilateral hand movement helps prepare the brain for literacy tasks afterward. It can be a fun icebreaker, or way to begin your instruction.

5. The Name-and-Notice Breath: Interoception as a Safety Anchor

Breathing strategies only work when a child feels safe enough to access them, and this is where interoception — the ability to notice internal sensations — becomes essential. When a student places one hand on their chest and the other on their lower ribs, the touch itself becomes the first cue of safety. Polyvagal-informed practice shows that gentle self-contact can help the body shift out of defensive states because it brings awareness back to the core of the body rather than the chaos of the moment.

The invitation is simple: “Just notice what your hands feel like.” There’s no requirement to breathe a certain way or think a certain thought. Once the child’s attention turns inward, the breath naturally begins to deepen. This soft, physiological change is enough to support vagal pathways involved in calming the system. Teachers often see the child’s face soften or their shoulders release as interoception helps the nervous system regain its footing.

The goal isn’t perfect breathing; it’s reconnection. When a student can feel even a hint of their own breath and body again, they move closer to ventral vagal, where emotional waves settle and the mind becomes available for learning. It’s a small practice with a surprisingly steady impact.

Why Micro-Regulation Matters More Than We Think

Micro-regulation practices may be small, but their impact grows quickly. Each one gives the nervous system a brief moment to settle, reorganize, and come back into the present moment. When a child has access to that kind of support, their body softens, their emotional wave moves through, and they can rejoin learning without feeling overwhelmed by what just happened. The more we teach this now, the better it will be for their future as well. Imagine a world where people have the tools and self-awareness to regulate.

These quick resets also help shape the feel of the classroom over time. When students experience regular, simple moments of grounding, they begin to recognize what safety feels like inside their own bodies. They learn how to return to themselves when things get big. And teachers feel the difference too — the room holds more steadiness, more ease, and more capacity for connection.

That’s what micro-regulation really offers: small moments that gradually build a more regulated, responsive learning environment. Nothing dramatic or forced. Just gentle, steady nervous system support that keeps everyone anchored enough to move forward together.

A Simple Way to Get Started

If micro-regulation feels helpful but hard to translate into the flow of a busy day, I created a short guide to make it easier.

The Free Micro-Reset Guide walks through five simple nervous system strategies that can be used in under two minutes—no special materials, no prep, no disruption.

These are small, practical resets designed for real classrooms. The kind that help students settle, help teachers feel more resourced, and quietly shift the tone of the room over time.