How Dysregulation Shows Up In Students

You've seen it. The student who was fine five minutes ago is now struggling over something that seems small. The kid who asks to go to the bathroom for the third time during math. The one who sits frozen at their desk while everyone else is working. The child who can't stop apologizing for everything.

We’re often quick to label these as behavior problems. But what if there is something else driving them? Something physiological. When kids feel overwhelmed, anxious, scared, or stressed (and elementary-aged kids feel these things A LOT), their bodies activate survival responses that literally hijack their ability to learn, think, and make good choices. So these are nervous system issues that are showing up in real time and in real ways in our classrooms.

And when we understand how these five stress responses show up, we change how we interpret behavior and also the strategies that we call upon to help our students.

Fight: The Kids Who Come Out Swinging

You know this one. Fight shows up as aggression, opposition, and outbursts. These are the students whose big emotions come out sideways, and it can feel challenging to navigate.

Here's what you're actually seeing:

During morning work, Jayden breaks his pencil. You hand him a new one. He breaks that one too. Then he rips his paper in half, shoves his workbook onto the floor, and when you approach, he yells "I HATE THIS!" You haven't even started teaching yet.

At the carpet, you ask everyone to sit criss-cross. Mia immediately shoots back: "Why do we HAVE to?" You redirect. She argues again. You give a choice. She argues with the choice. Every. Single. Direction. becomes a negotiation or a fight.

In line for lunch, two kids bump into each other accidentally. Before you can even process what happened, one of them has shoved the other into the wall. Hard. Over nothing.

During a transition, you ask the class to clean up centers and move to their desks. One student—who seemed fine seconds ago—suddenly sweeps everything off the shelf, knocking blocks and toys everywhere, face red with rage.

At recess, a kindergartener hauls off and hits another kid because they took "their" swing. No words, no warning, just immediate physical aggression.

During independent reading, a fourth grader slams their book shut and mutters under their breath (loud enough for you to hear): "This is stupid. You're stupid. I'm not doing this." When you address it, the volume and intensity escalate fast.

Fight looks like anger and defiance, but underneath it's actually fear and overwhelm. That child's nervous system has decided that aggression is the only way to protect themselves. Which is why its so imperative that we reframe this from students are giving us a hard time and recognizing that they are having a hard time.

Flight: The Kids Who Are Always Trying to Escape

Flight is all about avoidance. These kids' nervous systems have decided that getting away is the safest option, and you'll see them constantly trying to escape—physically, mentally, or both.

Here's what you're actually seeing:

During math, the same student asks to go to the bathroom. Again. It's the third time this block, and it's always during independent work time. Never during the mini-lesson when they're sitting safely with the group. Always when they have to do something hard alone.

At your small reading group, a first grader keeps dropping things—their pencil, their eraser, their book—and crawling under the table to get them. They're under there more than they're in their seat.

During writing workshop, a second grader suddenly announces they need to go to the nurse. Their stomach hurts. Or their head. Or they feel dizzy. The symptoms are real to them, but they happen with remarkable consistency during specific activities.

In the middle of a lesson, a kindergartener just... leaves. Gets up and walks out of the classroom. No asking, no warning. You find them in the hallway, in the bathroom, or hiding in the reading corner of another classroom.

During centers, one student never actually completes a center rotation. They're constantly up—sharpening their pencil (that doesn't need sharpening), getting a tissue, asking for a different material, reorganizing their pencil box. Their body cannot be still because their nervous system is screaming "run."

When you announce a test or quiz, an eight grader who's been at school all week suddenly has a pattern of being absent on test day. Or they're 30 minutes late. Every. Single. Time.

During any challenging task, a student creates elaborate distractions—suddenly they NEED to finish this drawing, or they start a completely different activity, or they engage the kid next to them in an intense conversation about what they did last weekend. Anything but the actual assignment.

Flight looks like the kid is just trying to get out of work, but their nervous system has genuinely identified the situation as threatening and is doing everything it can to escape.

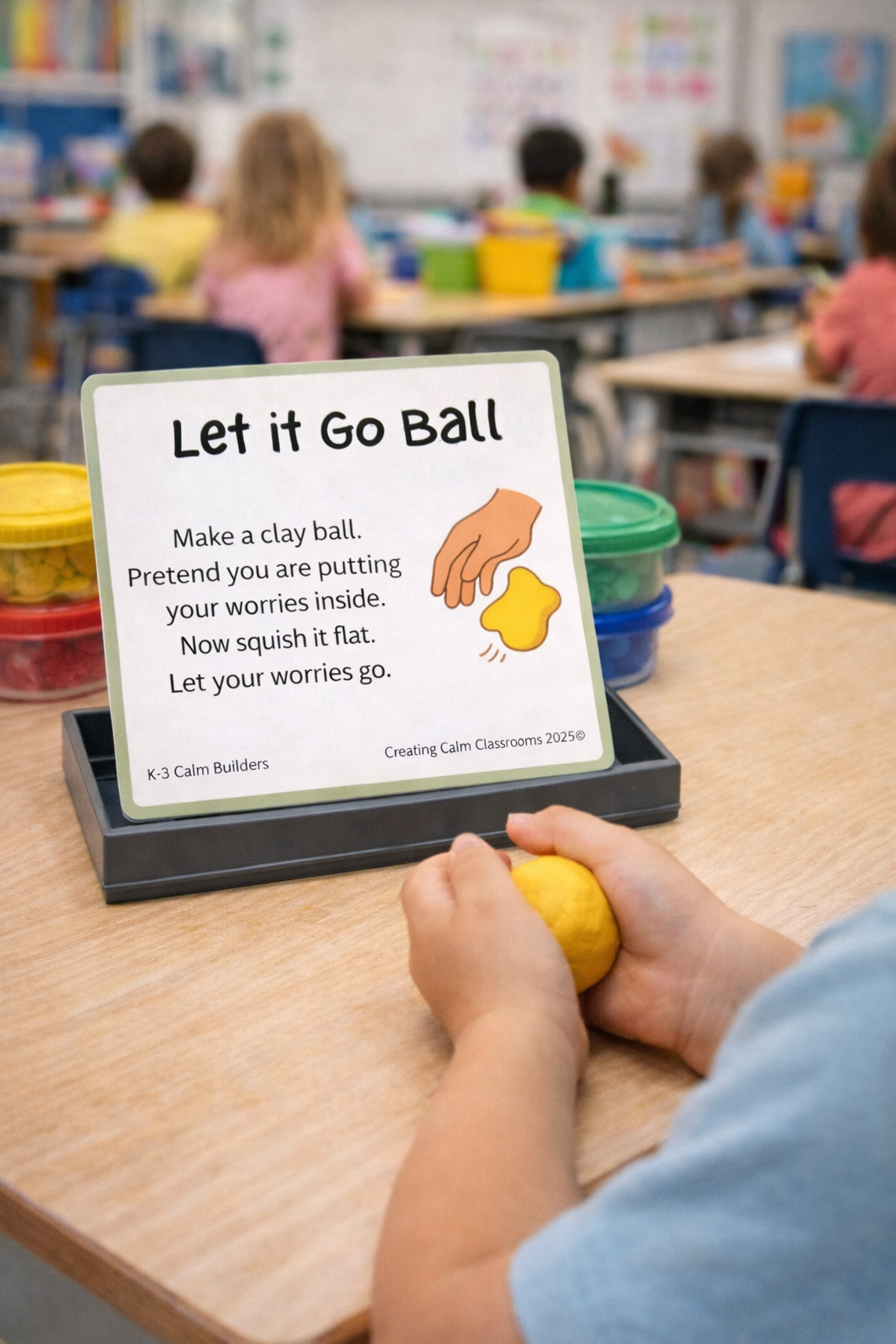

Build Regulation into the Day with our STEM and Clay Based Regulation Prompt Cards!

Freeze: The Kids Who Disappear While Sitting Right in Front of You

Freeze is the trickiest one to spot because these kids don't cause any disruption. They're quiet. They're not bothering anyone. But their nervous systems are completely locked up, and they've essentially left the building even though their body is still in the chair. And the worst part is, these are the students we praise for always being quiet.

Here's what you're actually seeing:

During independent work time, a student is staring at a blank piece of paper. Ten minutes pass. Fifteen. Twenty. Their pencil hasn't moved. The paper is still blank. They're not looking around, not fidgeting, just... frozen.

When you call on them during a discussion, they look up at you with huge eyes and say absolutely nothing. The silence stretches out painfully. You wait. You prompt. You try to help. Nothing. They just stare at you like a deer in headlights, unable to produce words even though you've heard them answer questions before.

At the carpet during read-aloud, one child is physically present but their eyes are glazed over, staring at nothing. You can tell they're not tracking the story, not following along. It's like they've gone somewhere else entirely while their body stayed put.

During morning meeting, a kindergartener who chatters away at recess becomes completely nonverbal. They can't answer when it's their turn to share. They can't say good morning back. It's not shyness—it's a complete shutdown of their ability to speak.

When the class transitions to the next activity, one student doesn't move. Everyone else has cleaned up and moved on, but they're still sitting in the exact same position. You give a reminder. Then another. Five minutes later, they still haven't moved. It's not defiance—they genuinely seem unable to initiate the movement.

During a fire drill or an unexpected loud noise, a first grader goes completely rigid—shoulders up, body stiff, unable to move or respond to instructions. While other kids are lining up, this one is stuck.

In your guided reading group, a student stares at the page but can't seem to make their mouth work to read the words. Long, painful pauses. Eventually they might whisper something, but it takes forever and looks almost physically difficult for them.

Freeze often looks like a child is spacing out or being defiant, but their nervous system has actually put them in lockdown mode. They're not refusing—they literally can't.

Fawn: The "Perfect" Kids Who Are Terrified of Disappointing You

Fawn is the response that often gets missed because these kids look like model students. They're helpful, compliant, eager to please. But underneath all that people-pleasing is a nervous system that believes their safety depends entirely on keeping you happy.

Here's what you're actually seeing:

Throughout the entire day, a second grader says "I'm sorry" constantly. Sorry for asking a question. Sorry for needing to sharpen their pencil. Sorry for breathing too loud. They apologize for things that aren't even problems, aren't even their fault, or didn't even happen.

During independent work, a third grader brings you every single answer before writing it down. "Is this right?" "Is this okay?" "Are you sure this is good?" They can't trust their own thinking and need you to validate every move they make.

In partner work, one student ends up doing all the work for both kids. Their partner is goofing off or not contributing, but this child just does it all without complaint because they cannot handle the anxiety of potential conflict or your potential disappointment in the group.

When you ask them to choose, they can't. "Where do you want to sit?" "I don't care, wherever." "What book do you want to read?" "Anything is fine." "Which center do you want to start with?" "Whatever everyone else picks." They've learned that having preferences is dangerous.

During every cleanup time, the same kid is frantically picking up—not just their area, but everyone else's too. They're practically climbing over other students to put away materials, reorganize shelves, wipe down tables. They need to be helpful.

When there's a conflict at recess, a kindergartener immediately takes the blame even though three other kids saw that they weren't involved. "It's my fault. I'm sorry. I'll fix it." They absorb responsibility like a sponge.

In your classroom, you have one student who is hypervigilant about your mood. If you seem even slightly frustrated (not even at them), they immediately shift their behavior, become quieter, work harder, glance at you nervously to make sure you're okay. Your emotional state becomes their job to manage.

At the end of the day, a first grader lingers to help you clean up, organize, carry things—not because they love helping, but because they need to prove their worth through service.

Fawn looks like the dream student, but these kids have learned that their value is entirely dependent on keeping everyone around them happy. Their nervous system has decided that pleasing people is survival.

Flop: When Kids Completely Shut Down

Flop is the most extreme stress response and the one that can honestly be scary to witness. This is total system shutdown—the nervous system's emergency off switch. These kids aren't being lazy or giving up. Their bodies have literally pulled the plug.

Here's what you're actually seeing:

In the middle of a math lesson, a student who was participating just fine suddenly puts their head down on the desk. You try to gently check in, but they don't respond. They're not asleep—their eyes might even be open—but they're completely unreachable. It's like someone turned them off.

During a meltdown, a kindergartener goes from screaming and thrashing to suddenly collapsing on the floor like a ragdoll. They just... drop. Their body goes completely limp and they can't or won't get up.

At morning meeting, a first grader slides out of their chair onto the carpet and just lies there. Not moving. Not responding when you call their name. They're staring at the ceiling or at nothing at all.

During a stressful transition (fire drill, surprise assembly, unexpected schedule change), a second grader who was fine before suddenly looks pale, complains of feeling dizzy or sick, and seems like they might pass out. The physical symptoms are real—their nervous system is creating them.

In the middle of independent reading, a third grader's eyes start closing. Not because they're tired—they got plenty of sleep—but because their body is literally trying to shut down. Within minutes they're actually asleep at their desk in the middle of the day.

During a challenging activity, a student becomes completely non-responsive. You're asking them questions, giving gentle prompts, but it's like they can't hear you. They're physically present but mentally gone—dissociated, checked out, unreachable.

After a big emotional moment, a child who was just crying or upset goes completely flat. No expression, no movement, no engagement. They're not calm—they're shutdown. There's a huge difference.

Flop looks like the kid has given up or is being difficult, but what's really happening is their nervous system has decided that complete shutdown is the only way to survive what feels overwhelming. This is your body's last-ditch effort at protection.

Why This Matters for Your Classroom

Once you start seeing these patterns, you can't unsee them. That student who challenges every instruction? Fight response. The one who asks to go to the bathroom for the fourth time? Flight. The quiet one who never finishes their work? Freeze. Your helper who can't stop apologizing? Fawn. The child who randomly shuts down? Flop.

None of these are choices. They're not manipulations. They're not behavior problems that need consequences. They're automatic nervous system responses to stress, overwhelm, fear, or perceived threat. And in elementary school, kids' nervous systems are perceiving threat A LOT—new routines, academic pressure, social conflicts, sensory overload, big emotions they don't have words for yet.

Here's what changes when you recognize dysregulation:

You stop taking it personally. When a first grader tells you they hate you during a meltdown, you understand their fight response is activated and it's not actually about you.

You stop seeing defiance everywhere. When a third grader won't start their work after you've asked five times, you recognize freeze instead of assuming they're being stubborn.

You stop rewarding kids whose nervous systems are screaming. When your "best" student apologizes for the tenth time that day, you see fawn instead of compliance.

You start looking for patterns. You notice that flight always happens during math, or freeze shows up every time there's a substitute, or fight appears during transitions.

You start asking different questions. Not "What's wrong with this kid?" but "What's happening for this kid right now? What is their body trying to tell me?"

The behavior you see in your classroom—the aggression, the avoidance, the shutdown, the people-pleasing, the collapse—is not the problem. It's the solution a young nervous system has created to handle situations it perceives as threatening or overwhelming.

Your job isn't to fix these kids or make the behaviors stop. Your job is to see them clearly, understand what their nervous systems are doing, and recognize that the most challenging students are often the ones whose bodies are working the hardest to keep them safe.

That recognition? That's where everything starts to shift.

Nervous System Literacy for Educators

launching February 2026

A practical masterclass for educators who want to reduce stress, protect their capacity, and teach from a regulated place.